Today, #Norinchukin Bank is starting to be less of an obscure name compared to more than 7 months ago when the #FED quietly added it to the list of counterparts eligible to access the standing Repo Facility the central bank established with the purpose of dealing with emergency liquidity shortfalls in systemically important institutions (WHY IS THE FED PREPARING TO BAIL OUT A JAPANESE BANK?).

What was Norinchukin’s big mistake? To have heavily invested in long-duration bonds and credit instruments when rates were low across the globe without an effective hedging strategy in place since they were so sure rates would have remained low for such a long time (hence no need to pay for insurance and trim the bottom line). The bank is blaming higher interest rates’ impact on the value of its government bond holdings as the cause of its losses, but why don’t they simply hide them in their “Hold To Maturity” books like everyone else does? The answer is very straightforward because clearly they are being forced to sell those government bonds at a loss.

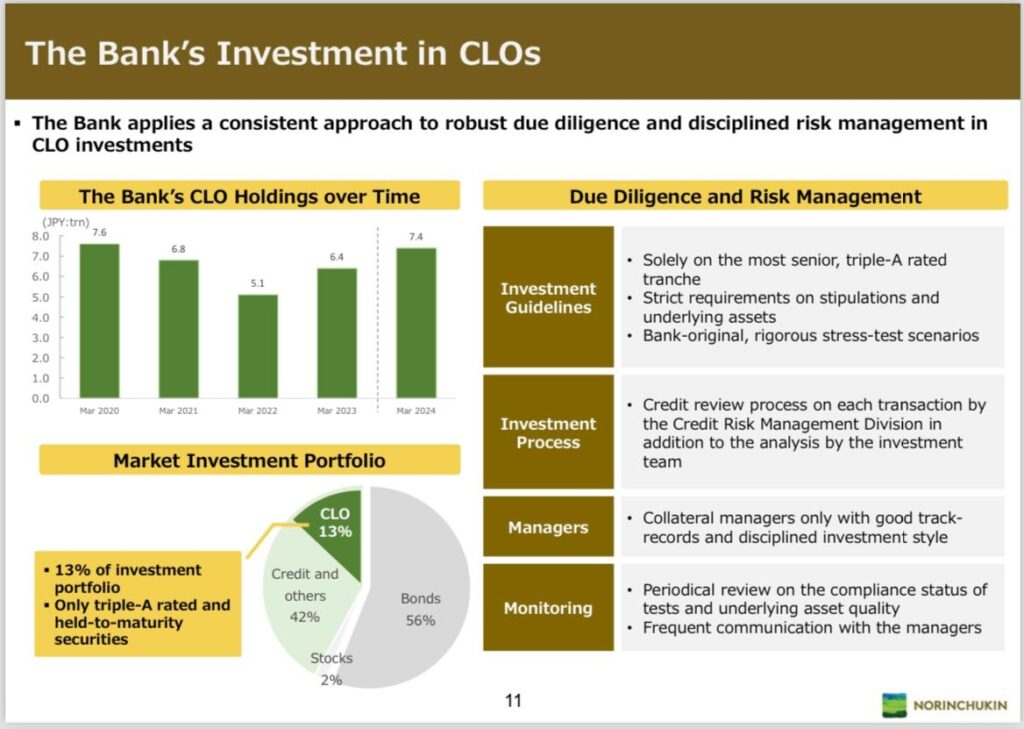

As you can see from the slide below from the bank’s latest financial presentation, CLOs represent 30% of Norinchukin’s total “Credit” investments that alone account for 42% of Norinchukin’s portfolio.

Yes, I know what you are thinking at this moment: “if those AAA CLOs are of such high quality and not bearing losses as Norinchukin claims, why not sell those instead of $63bn of practically risk-free government bonds that will repay at par as long as they are held till maturity?” [Norinchukin Bank to Sell $63 Billion of Sovereign Bonds]

This is the answer:

1 – It is an open secret that CLOs and other Credit investments such as MBS and CMBS are carrying even larger losses, so better to keep them “hidden” in the HTM books.

2 – There aren’t many buyers for radioactive assets, especially CLOs, available in the market at the moment.

Now, the BOJ and the Japanese authorities are making sure the MSM narrative treats Norinchukin as an isolated case that is being managed and will be dealt with without contagion to other banks in the local and potentially global system. However, the truth is there are many other “Norinchukins” out there because for many years every major Japanese financial institution was focused on deploying capital abroad (most of that #JPY printed out of thin air by the #BOJ) since it was effectively illogical to invest at rock-bottom rates at home. Among all of them, if Norinchukin was the “queen” then Japan Post Bank could be considered the “king.”

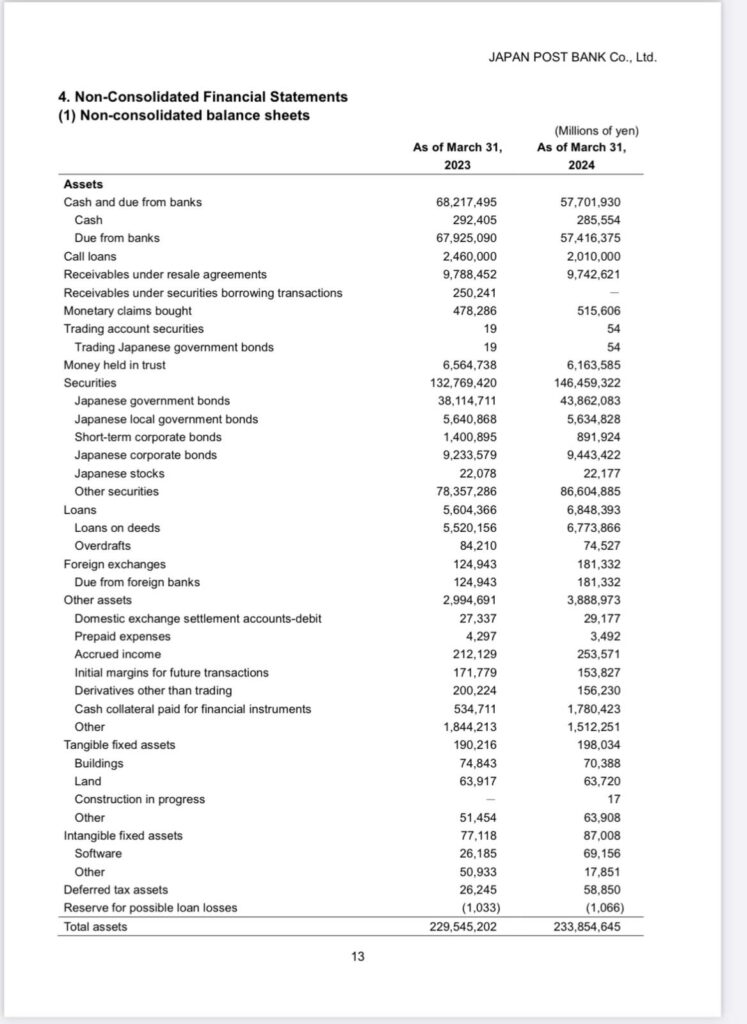

As you can see from the latest financial statements, 37% of Japan Post Bank’s assets are invested in “Other Securities”

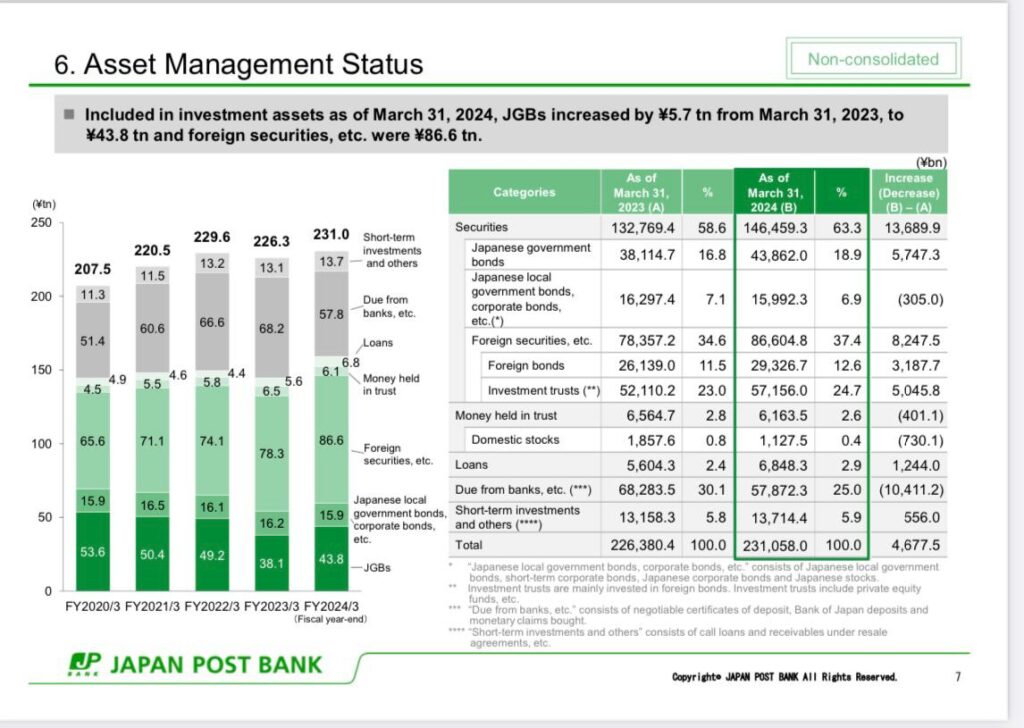

What are those “other securities”, we don’t find the answer in Japan Post Bank’s financial statements, but in its investors’ presentation and the answer is 29.3 Trillion #JPY of “Foreign Bonds” and 57 Trillion #JPY of “Investment Trusts” that according to the barely readable footnote in light grey at the bottom of the table “are mainly invested in foreign bonds, private equity funds, etc.”

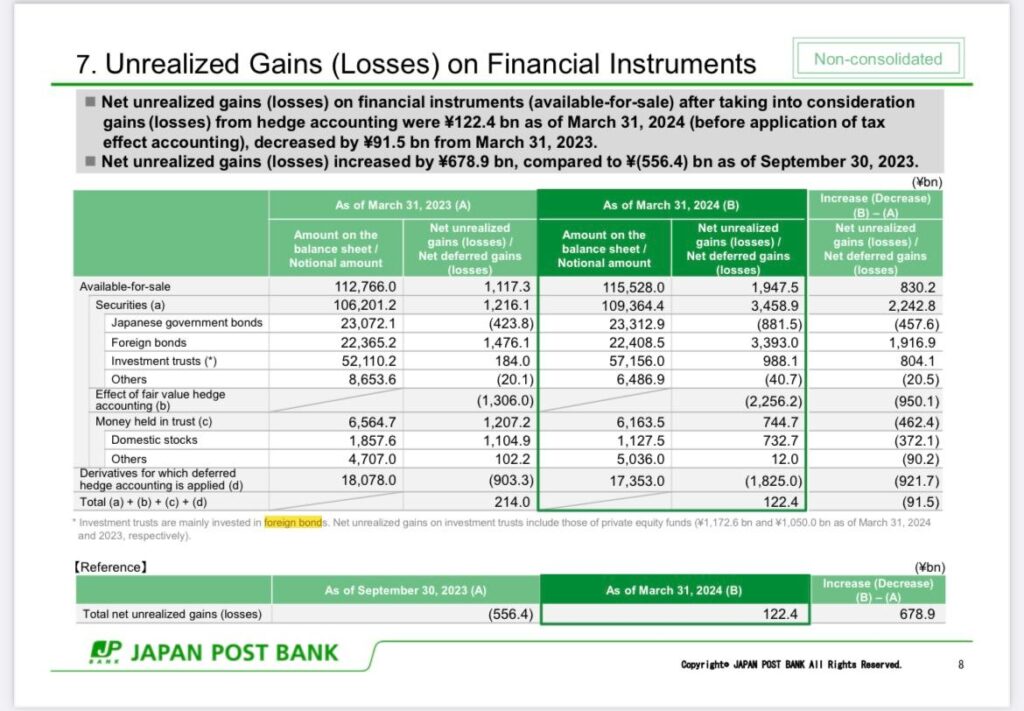

Now tell me, how is it possible that, while Norinchukin Bank is dealing with steep losses in its foreign bond investments, Japan Post Bank is claiming an unrealized capital gain of more than 10% on those? How is it possible that a gain is also being marked for “Investment trusts” mainly invested in foreign bonds and private equity funds? Of course, it’s not possible considering the two banks operate in the same planet Earth, and share a similar balance sheet structure and asset management approach…

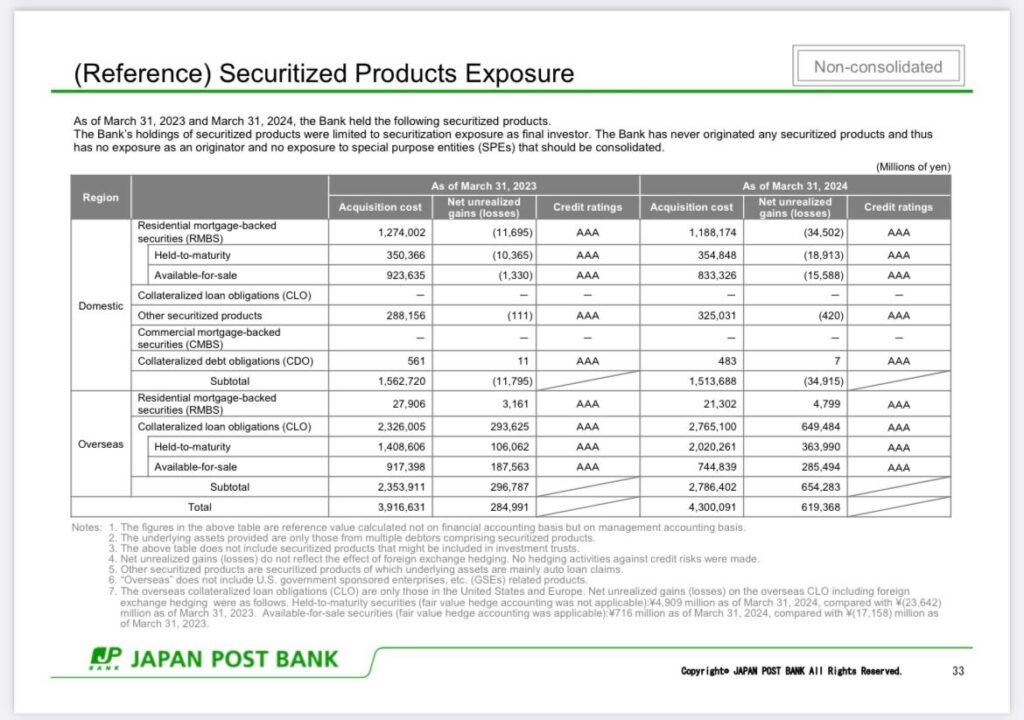

Since unicorns from a fantasy world populate Japan Post Bank’s accounting department, apparently the bank is also marking a profit on its CLOs and securitized product investments while Norinchukin does not.

To conclude, Japan Post Bank holds 86 trillion #JPY of assets reasonably bearing a significant amount of “paper” (so far) losses against just a little less than 10 trillion #JPY of capital. Yes, they hold double the amount of capital than Norinchukin but they are also carrying double the risk, and overall its balance sheet is double of Norinchukin’s size, so relatively speaking they are roughly in the same situation. How long before the market stops believing in its accounting unicorns and starts realizing there is an even bigger problem here?