Why did the South Korean financial services regulator commence investigations into potential illegal naked short selling? In September 2023, over 50,000 citizens, frustrated with their losses in the Korean stock market, petitioned the government to investigate unfair trading practices, especially naked short selling, purportedly carried out by brokers and banks. Given the upcoming elections and the risk of popular backlash from disregarding the request, the government acquiesced, and the regulator began its investigation in October 2023: FSS launches probe into global banks over illegal short selling.

What did the Korean regulator (FSS) uncover? First, it didn’t take long to encounter illegal trades; secondly, these trades were executed abroad, particularly in Hong Kong. Is anyone surprised so far? I think not. Let’s proceed.

According to the FSS, “One of the two brokerages [HSBC] illegally shorted 101 stocks with transactions totaling 40 billion won ($29.6 million) between September 2021 and May 2022. The other [BNP] did the same with nine stocks for 16 billion won during the August-December 2021 period while hedging its swap contracts with overseas funds.”

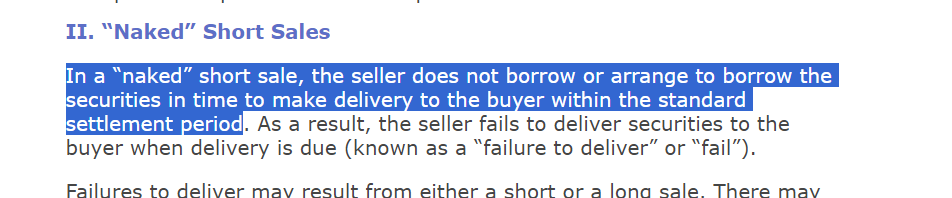

Hang on, is that short-selling for ants? How could these piddly transactions influence an entire market? Now, it’s crucial to understand a significant part of the regulation: Naked short selling involves making a short sale without borrowing the stocks, or determining that the stocks can be borrowed, before selling them off.

LOOPHOLE #1

That tiny yet massively significant loophole has been shrewdly incorporated into stock trading rules globally. Below is an example from the #SEC rules.

So, what does “determining that a stock can be borrowed” mean? To comply with #SEC rules (more or less the same in other jurisdictions), these are the criteria to meet:

- Locate Requirement: Before executing a short sale, brokers and dealers must have reasonable grounds to believe that the security can be borrowed so that it can be delivered on the delivery date. This is known as the “locate” requirement.

- Affirmative Determination: This involves obtaining a “locate” from a suitable source, such as a stock lending department or an external lender, confirming that the shares are available to borrow. This step ensures that the short seller will be able to deliver the shares when required.

- Documentation: The broker or dealer must document how they determined that the security could be borrowed. This can include records of communications with lenders or internal records from stock lending systems.

- Compliance: Fulfilling this requirement is essential to comply with SEC regulations and avoid violations such as naked short selling, which occurs when a short sale is executed without first borrowing the security or ensuring that it can be borrowed.

All of the above can be achieved with a small action in practice, such as picking up the phone (on a recorded line) and asking your stock lending/borrowing desk, regularly in touch with large asset managers, if anyone is available to lend stock XYZ. In over 90% of cases, the answer from the client is “yes”. Large asset managers are usually quite happy to lend out their stocks as it generates “extra yield” for them without altering their asset allocation or strategy.

I intentionally said “in ~90% of cases,” since sometimes even large asset managers might not have available stocks to lend or be willing to do so (for example, when they do not trust the broker’s solvency, but that’s a story for another day). So what about the remaining 10%?

LOOPHOLE #2

According to the SEC itself: “In certain circumstances, naked short selling contributes to market liquidity. For example, broker-dealers that make a market in a security generally stand ready to buy and sell the security on a regular and continuous basis at a publicly quoted price, even when there are no other buyers or sellers. Thus, market makers must sell a security to a buyer even when there are temporary shortages of that security available in the market. This may occur, for example, if there is a sudden surge in buying interest in that security, or if few investors are selling the security at that time. Because it may take a market maker considerable time to purchase or arrange to borrow the security, a market maker engaged in bona fide market making, particularly in a fast-moving market, may need to sell the security short without having arranged to borrow shares. This is especially true for market makers in thinly traded, illiquid stocks as there may be few shares available to purchase or borrow at a given time.“

I hope many of you did not skip a heartbeat, particularly #GME shareholders, in reading the above. Yes, people, if the market maker is acting in “bona fide” just to do his job in providing “liquidity” to the market, making it more “efficient,” then they are still within the boundaries of the law.

Summarizing SEC rules, a market maker can demonstrate they acted in “bona fide” by maintaining regular and continuous quotations, focusing primarily on market-making activities, being active in a reasonable number of securities, providing quotes consistent with market conditions, avoiding manipulative practices, keeping thorough records, and complying with all relevant SEC regulations.

LOOPHOLE #3

If loopholes #1 and #2 weren’t sufficient, loophole #3 covers even the remaining cases in which a market maker fails to deliver, thus potentially flagging the risk of a “naked” short selling having taken place.

According to the SEC: “A failure to deliver occurs when a broker-dealer fails to deliver securities to the party on the other side of the transaction on the settlement date. There are many justifiable reasons why broker-dealers do not or cannot deliver securities on the settlement date. A broker-dealer may experience a problem that is either unanticipated or is out of its control, such as (1) delays in customers delivering their shares to a broker-dealer, (2) the inability to obtain borrowed shares in time for settlement, (3) issues related to the physical transfer of securities, or (4) the failure of a broker-dealer to receive shares it had purchased to fulfill its delivery obligations. Failures to deliver can result from both long and short sales“

What happens then? At this point, in theory, the clearing house must act and buy/borrow the shares from the market to address the failure to deliver. However, there are plenty of ways to still meet clearing requirements without breaking the law (though standing at the very edge of them):

- Exemptions for Market Makers for very illiquid securities (as discussed above).

- “Good Until Canceled” Orders: Orders that remain open until canceled (GTC orders) can be used to create an appearance of continuous trading activity without actual execution, potentially influencing stock prices or trading behavior without immediate settlement obligations.

- Rehypothecation: Shares borrowed for short selling can be lent out multiple times (rehypothecation), which can lead to a situation where the same shares are effectively counted multiple times, complicating the actual delivery of shares.

- Derivatives: Participants might use complex derivatives or synthetic positions to replicate short selling without the same regulatory scrutiny or delivery obligations, potentially leading to hidden or delayed FTDs.

- International Arbitrage: Some market participants may exploit differences in regulations between countries to engage in practices that would not be allowed in more strictly regulated markets, effectively using international arbitrage to avoid regulatory constraints (like short selling Korean stocks from Hong Kong as we discussed above).

- Hidden Ownership and Beneficial Ownership Chains: Complex ownership structures and chains of beneficial ownership can obscure the true owners of securities, making it challenging for regulators and clearinghouses to track and enforce delivery requirements accurately.

At this point, it might not be surprising that the Korean regulator managed to gather solid evidence of illegal naked short selling only on a very limited number of transactions, and this came at a great expense of effort and resources. Imagine a much larger market like Europe or the US; do you believe the SEC’s 4,807 employees are enough to go after everything that goes on at the very edge of the law? Furthermore, considering all I described above, even after the SEC stumbles on a blatant case of illegal activity, with all the loopholes in place, what are the chances they can gather enough strong evidence to prove illegal activity took place? I regret to say, but as proven by the Korean case, in the current market, there is very little that can be done against illegal naked short selling if the current laws remain in place and the monitoring technology does not keep pace with the evolution of the one employed by hyper-sophisticated brokers and hedge funds supported by armies of lawyers.