While doing my best to untangle the mess of the Bank of Japan (BOJ), in particular, to figure out which financial institution/s could be in danger after what happened on Monday this week, I stumbled upon something very interesting. Please have a look.

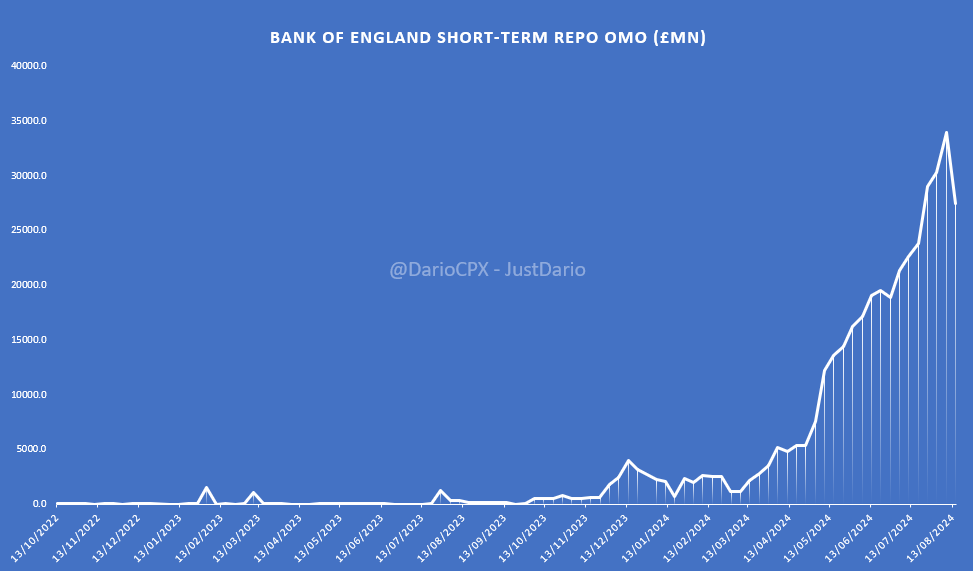

This chart represents the Bank of England (BOE) Short-Term REPO facility which is described as:

“The STR allows participants to borrow central bank reserves for a one-week period in exchange for high-quality, highly-liquid (Level A) assets.

This facility is priced at Bank Rate. Combined with the one-week term, this helps keep short-term market interest rates in line with Bank Rate by ensuring banks have little need to pay above Bank Rate for reserves in money markets.

There is an unlimited supply of central bank reserves available in the operation to ensure that banks’ demand for reserves continues to be met as QE unwind progresses.”

Now, suppose my understanding of English is still decent and considering the almost parabolic spike in volumes drawn by banks from this facility. In that case, it looks like we have a bit of a liquidity problem in the UK.

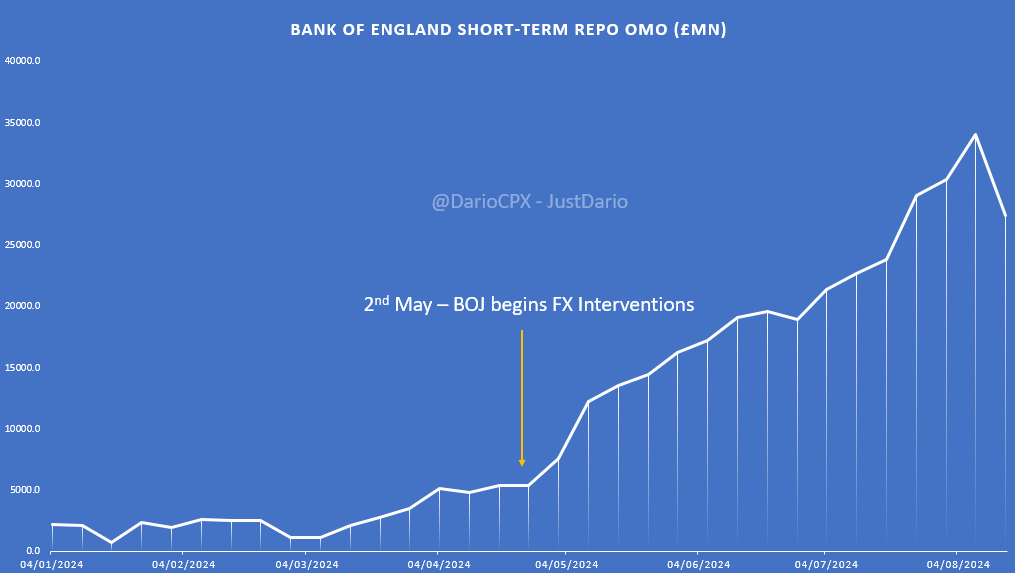

At this point, after looking closer into the volumes of this facility, I discovered something very interesting and I highlighted it to help you see what I saw.

Shocking, isn’t it? Here you have the perfect example of how the JPY carry trade became such an integral part of the global financial system with repercussions reaching far beyond Japan.

Alright, what’s happening here? It’s no mystery that the link between the UK and Japan became stronger after 2008 when Nomura acquired the non-US operations of the disgraced Lehman Brothers, which were located both financially and operationally in the UK. It is also no mystery that foreign banks and brokers run very large operations in Japan (for many of them it is even the second “profit center” globally). While many erroneously assume that a Central Bank accepts as collateral only bonds issued by its own government in order to lend temporary liquidity into the system, in reality, this is not the case as you can see here.

For short-term REPO operations, BOE accepts only “Level A” collateral, let’s take a closer look at what that means:

“Sterling, euro, US dollar and Canadian dollar denominated securities (including associated strips) issued by the governments and central banks of the UK, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands and the United States”

Yes, my dear readers, you can borrow GBP from the BOE tendering non-UK collateral, in particular US Treasuries.

Wait, why isn’t Japan there? Apparently, the BOE considers Japanese Government Bonds a “Level B” type of collateral:

“Sovereign and central bank debt (including associated strips), of Australia, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland, issued either in the domestic currency or in sterling, euro or US dollar”

Putting all the pieces of the puzzle together, at this point, it should be pretty obvious how banks have been pulling liquidity out of the BOE to absorb the drain in their books caused by the unwinding of the JPY carry trade that effectively removed a good chunk of leverage from the system. Wait, isn’t that supposed to be a zero-sum game for banks and brokers? In theory, yes, in practice, if the clients you sit in the middle and help facilitate trades start not having cash to settle their transactions, the bank is liable to cover the shortfall first and then go after the client that is defaulting on its obligations. The consequence of this is a liquidity gap that needs to be filled in the system. What if the client in trouble ends up not paying the bank? Well, the bank at the point takes the hit right into its capital.

Why is this specifically happening in London and not Japan or the US? The answer is straightforward because the vast majority of OTC derivatives are booked by banks and brokers onto their UK legal entities. This is a result of a particularly accommodative UK regulatory system regarding derivatives that allows banks to post a very small amount of capital in their books despite dealing with huge volumes in the space. What’s the rationale? To keep things simple, banks are supposed to “net” their flows and keep a very limited residual exposure. The problem is, in this incredibly complex web of transactions entangled between each other, if too many tiles come off, then everything has a very hard time keeping standing, similar to a Jenga tower. Furthermore, no one, including the regulator, has the full picture of it at any time. It is simply impossible to track with the current system in place as I already highlighted in “THIS IS NOT 1987, 2000, 2008 OR 2020, BUT A WHOLE NEW MARKET MONSTER”

After all we discussed this week, I believe there is no more doubt there is a “dead man walking” in the global financial system after Monday’s events. However, it is also clear there is an ongoing scramble to kick the can down the road as long as possible, hoping for a miracle to rescue all those involved.

However, as I explained yesterday, the longer the BOJ takes to stop the (liquidity) bleeding in the financial system caused by its reckless rate hike and series of FX interventions, the greater the damage. We see mounting signs of liquidity stress in the system (spike in the MOVE index, increase in Skew, gappy T-Bills trades in overnight hours, and so on) and even if investors love to ignore them in the same fashion they ignored those that anticipated last year’s US Regional Banks crisis and Credit Suisse implosion, at some point they will be forced to face reality because (black) holes in the financial system cannot be kept hidden forever.