The answer to any problem Japan faced in the past 3 decades was “let’s just print our way out of it” and every time the global financial system was more than happy to swallow every drop of freshly printed #JPY.

What were banks doing with all that money that “magically” fell into their pockets and carried no interest to pay for its use? They were using it to accumulate “low-risk assets”. This particular category of assets is considered so safe by the regulators that a bank is only required to hold very little capital against it. This created 2 worlds: the real one with real risks and the “regulatory” one where, as long as you ticked all the boxes, the regulator gave you so much leash you could practically do whatever you wished without fear of being bothered.

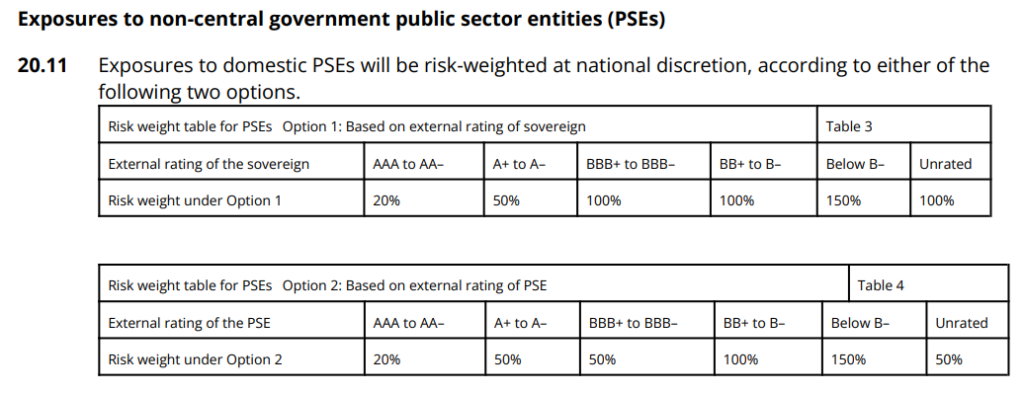

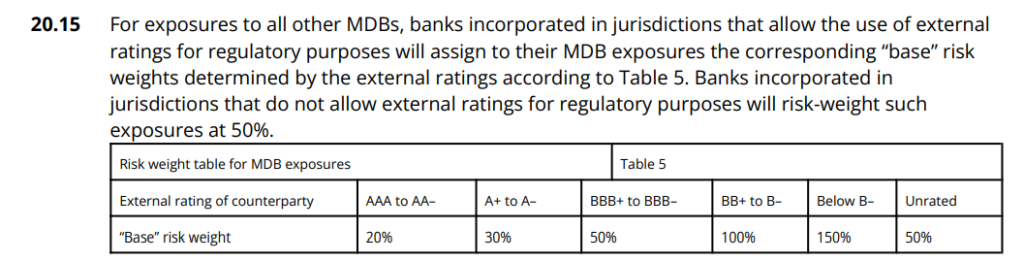

Now, please have a look at the 2 tables below included in the Basel Banking Committee CRE20 Framework (document):

The first table represents the risk framework Basel outlines for exposures toward Public Sector Entities (PSE), while the second represents the framework to be followed with regard to Multilateral Development Banks (MDB). Do you notice anything strange in the two tables? Yes, even if top rated (AAA to AA-) the RWA to be applied is not 0%, but 20%. Why? Very simple, even if publicly owned or supported by a group of sovereign countries, entities belonging to these 2 groups of risk DO NOT CARRY ANY EXPLICIT SOVEREIGN GUARANTEE. What does this mean? It means that the debt issued by these entities will not show up in the public debt of a country. All clear so far? I hope so because I will blow your mind now.

The open secret in the street is for governments to use PSE and MDB entities to issue debt in lieu of the country so the administration in charge has the resources to finance its spending budget without officially piling up sovereign debt. Why did banks start to lend hundreds of billions without any concern to these entities? Because no government will ever have the guts to not bail them out and make lenders, bankers call this “implicit guarantee”. Imagine what a great deal banks got, on one side you can earn a spread higher than government bonds, but on the other side, you virtually carry the same credit risk. Yes, this will cost you some capital, but if you have access to enough leverage at zero costs you can incredibly goose your ROEs carrying (virtually) no credit risk. This is exactly when the Bank of Japan’s reckless infinite QE policy of the past 3 decades became handy.

So banks started to pile up on JPY carry trades spreading liquidity across the world through PSE and MDB, except Japan (and the “experts” at the BOJ never understood this is why they kept seeing little to no effect of QE infinity on the Japanese economy).

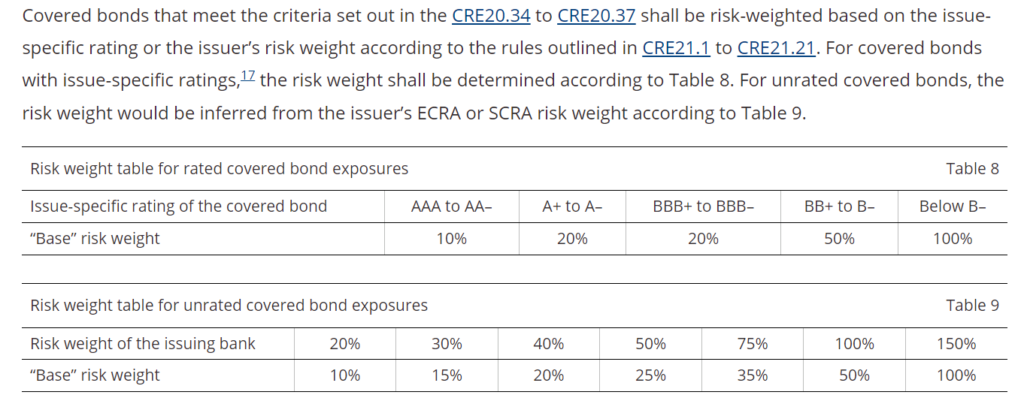

What do you think banks did when they lent so much to PSE and MDB to the point that their needs were saturated? As they always do, they started to go down the credit spectrum risk. In particular in one specific area: “covered bonds”.

What’s special about “Covered Bonds”? Well… let me show you the criteria a bond “covered pool” (the collateral) has to meet to fall into the category:

(1) claims on, or guaranteed by, sovereigns, their central banks, public sector entities or multilateral development banks;

(2) claims secured by residential real estate that meet the criteria set out in CRE20.71 and with a loan-to-value ratio of 80% or lower;

(3) claims secured by commercial real estate that meets the criteria set out in CRE20.71 and with a loan-to-value ratio of 60% or lower; or

(4) claims on, or guaranteed by banks that qualify for a 30% or lower risk weight. However, such assets cannot exceed 15% of covered bond issuances.

Isn’t it pretty obvious the massive “regulatory arbitrage” here? Yes, it is.

So basically banks needed 2 things: a constant supply of assets and low RWA requirements by the regulator. Banks found both in point (2) and (3) above. Do you know how many covered bonds guaranteed by Residential Real Estate or Commercial Real Estate received a rating below AA- (hence not so attractive for banks) when issued? Virtually zero. Yes yes I know, 2008 all over again.

I can continue very long to show how banks focused on finding loopholes in the Basel regulation to maximize their returns posting as little capital as possible, but I believe now you got my point.

So basically the Bank of Japan was an endless source of leverage for the global financial system and banks exploited it above and beyond any prudent limit. On paper, they all looked great for the regulator, then tell me how is it possible that one year ago Credit Suisse (a global systemic bank) needed a public bailout to avoid a dangerous Lehman-style implosion?

This is what you could read in Credit Suisse’s press release of 16 March 2023: “ As of the end of 2022, Credit Suisse had a CET1 ratio of 14.1% and an average liquidity coverage ratio1 (LCR) of 144%, which has since improved to approximately 150% (as of March 14, 2023). The use of the Covered Loan Facility of CHF 39 billion will further strengthen the LCR with immediate effect”

Woah a CET1 ratio of 14.1%! 150% LCR! Bananas bananas bananas.

Now that the #JPY carry trade is creating larger and larger holes in bank books ($JPY CARRY TRADE – THE BIGGEST FINANCIAL TICKING TIME BOMB OF ALL?), the next thing you are going to see is banks going after each other to claim the collateral they are owed to contain the damage and not being forced to start unwinding positions in the open market at a steep loss. Well… good luck with that!

In the era of wild asset rehypothecation, mounting volumes of “fail to deliver trades” in clearing houses across the world, shadow banks with no capital starving for liquidity (never forget banks were very happy to lend to Private Equities and Asset Managers as long as they pledged Residential or Commercial real estate assets as collateral) and derivative books of gargantuan sizes (MR. MARKET HAS BEEN FULLY REPLACED BY MR. DERIVATIVES – OH MAMMA MIA!), no bank can guarantee the numbers in their books are sound (exactly like in the case of Credit Suisse).