Three months ago, in “Why a Historical $JPY Currency Crisis Is at the Doorstep of Japan”, we discussed the precarious state of the Japanese yen (#JPY). Considering the volume of JPY printed, the size of Japan’s economy, and its foreign reserves, the yen should have been trading at 298 against the #USD, not around 155. Today, this calculation would result in an equilibrium rate of approximately 302, due to the Bank of Japan (#BOJ) burning through $62.2 billion of foreign reserves in its latest attempt to slow the yen’s free fall (Japan Spent Record $62 Billion in Past Month on Yen Intervention).

Even the mightiest Tom Cruise couldn’t accomplish the mission of salvaging the implosion of the JPY (Explaining and Simplifying the JPY – Counterintuitive – “Doom Loop”). Given the situation, we should examine how reality will catch up with what was once considered a “safe haven” currency.

To understand the situation better, let’s consider the typical phases of a currency implosion:

- Phase 1: Economic Mismanagement and Policy Failures

- Phase 2: Loss of Confidence

- Phase 3: Capital Flight

In Japan’s case, we are clearly transitioning from Phase 1 to Phase 2, with the BOJ’s verbal interventions becoming less effective both domestically and internationally. A “loss of confidence” typically manifests in two ways:

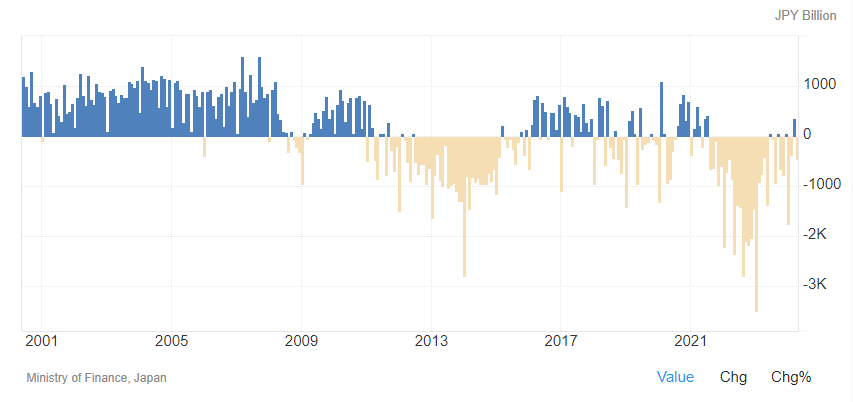

- A country’s trade balance (exports minus imports) deteriorates.

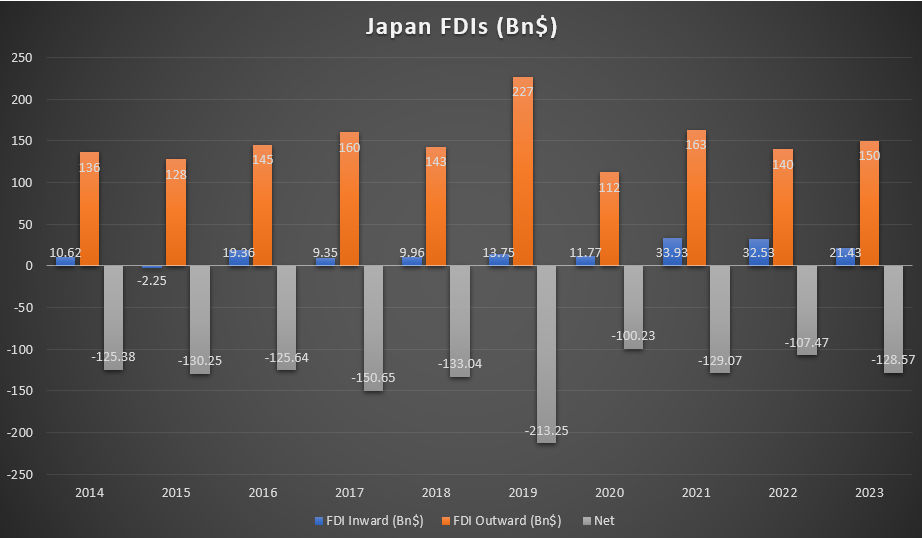

- Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) into the country become minimal.

Examining Japan’s trade balance trend over the past ~20 years reveals a long-term deterioration. The temporary improvement during the “Abenomics” period was short-lived, with Japan’s trade balance returning to negative territory well before the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020.

Regarding FDIs, Japan has consistently had higher outward FDI flows compared to inflows, signaling a reluctance from the international community to invest in the country.

Given Japan’s chronic inability to attract foreign investments and the unlikelihood of improvement, the trade balance will significantly influence the rate at which the JPY loses value.

Some argue that interest rate differentials between the USD and JPY will benefit the yen in the future, as the Federal Reserve is expected to cut rates while the BOJ may increase them. However, this perspective overlooks a critical point: as the BOJ allows Japanese interest rates to rise, more JPY will need to be printed to cover the increased cost of debt. If the BOJ tries to reduce its quantitative easing (QE) efforts, the government could quickly face insolvency, further eroding confidence in the JPY. Monitoring the growth of the BOJ’s balance sheet and Japan’s debt growth will be essential in gauging the speed of JPY’s decline.

How long will it take for a “loss of confidence” to trigger capital flight? It’s hard to predict. Sometimes it’s a slow process; other times, a “flight to safety” can quickly lead to the sale of a weaker currency in favor of a stronger one.

Between Phase 2 and Phase 3, I expect the JPY to behave similarly to the Turkish lira (TRY) in recent years, with large segments of the population converting their savings into more reliable foreign currencies, including cryptocurrencies. Once capital flight began, the TRY lost 75% of its value against the USD in just two years. If you think this can’t happen to Japan, remember that not long ago, few could have imagined such a future for Turkey’s monetary system.

To conclude, events can escalate rapidly for Japan, and no one should underestimate how quickly situations can evolve in today’s world.