Silver is garnering attention lately, with its price movements suggesting the onset of a short squeeze. Silver is no stranger to dramatic short squeezes.

The most notorious silver short squeeze took place in the late 1970s and early 1980s, executed by Nelson Bunker Hunt and William Herbert Hunt. These sons of Texas oil tycoon H.L. Hunt began buying substantial quantities of silver, expecting inflation to devalue paper currencies and silver to be undervalued. By 1980, they had stockpiled an estimated 100 million ounces of silver. This massive accumulation drove the price from approximately $6 per ounce in 1979 to a peak of $50 per ounce in January 1980. This accumulation led to a short squeeze as traders betting against silver were forced to cover their positions by buying silver at escalating prices. The squeeze concluded when the U.S. government and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) intervened, enacting new rules that limited the amount of silver contracts that could be purchased on margin. A similar event occurred during the 2008 financial crisis when silver experienced another, albeit smaller, short squeeze. As financial markets collapsed, investors sought refuge in precious metals. The price of silver increased from around $10 per ounce in late 2008 to nearly $50 per ounce by April 2011. This surge was partly fueled by investors covering short positions, propelling the price higher in a classic short squeeze.

Two class actions filed in the US and Canada accused UBS, Deutsche Bank (DB), HSBC, and Bank of Nova Scotia (BNS) of colluding to manipulate the price of silver, particularly suppressing it to profit on the short positions in their proprietary trading books, between 1999 and 2014. HSCB and BNS won the US lawsuit, with the judge ruling that despite proven price manipulation practices, “other economic factors” contributed to the fluctuations in silver prices.

This outcome was strange, considering that DB chose to settle and pay $38m to discreetly close the case (settlement here)

An important point to note here is that UBS, HSBC, BNS, and DB all belonged to “The London Silver Market Fixing Ltd”. This company was responsible for setting prices for various silver price benchmarks (the famous “silver fix”). This company was abruptly dismantled in 2014 after a campaign led by European regulators to crack down on silver price manipulation (Archive here)

Fast forward to today, even though “The London Silver Market Fixing Ltd” is history, four banks still indirectly control the price of physical silver in the market through the “London Precious Metal Clearing Limited”. These banks are HSBC, ICBC, UBS, and JP Morgan.

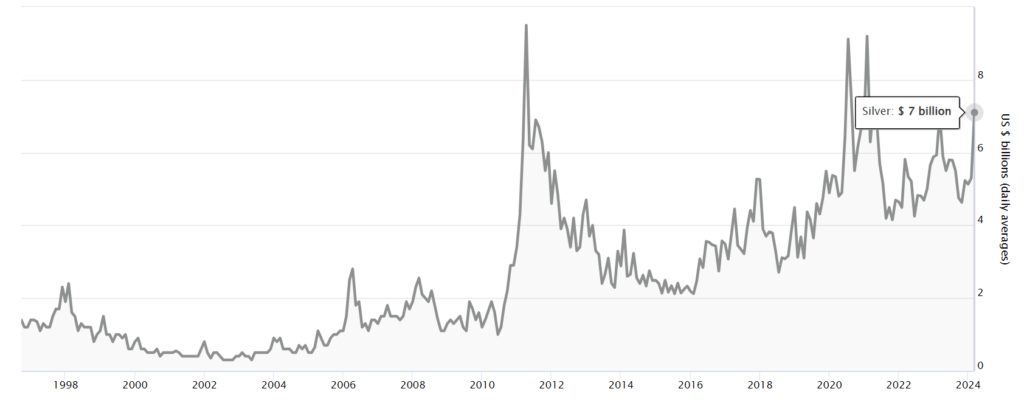

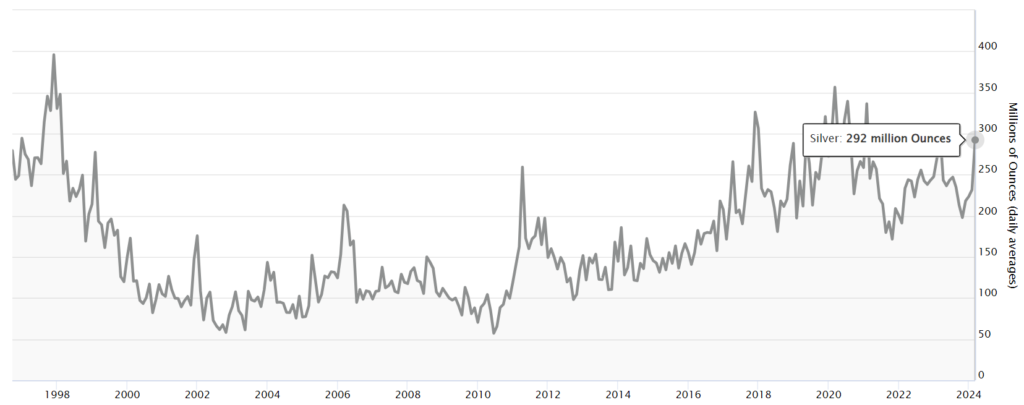

The two charts below reveal something peculiar happening according to LBMA data. The latest daily average of silver volume transfers into the vaults and managed by the Clearing has been reported at 292 million ounces against an average daily value of $7bn, indicating the latest daily average clearing price for silver is ~$24.

There is a small problem here. According to LBMA’s own silver fixing price, the latest value was $31.56, and the last time silver traded at $24 was… three months ago according to their own fixing price.

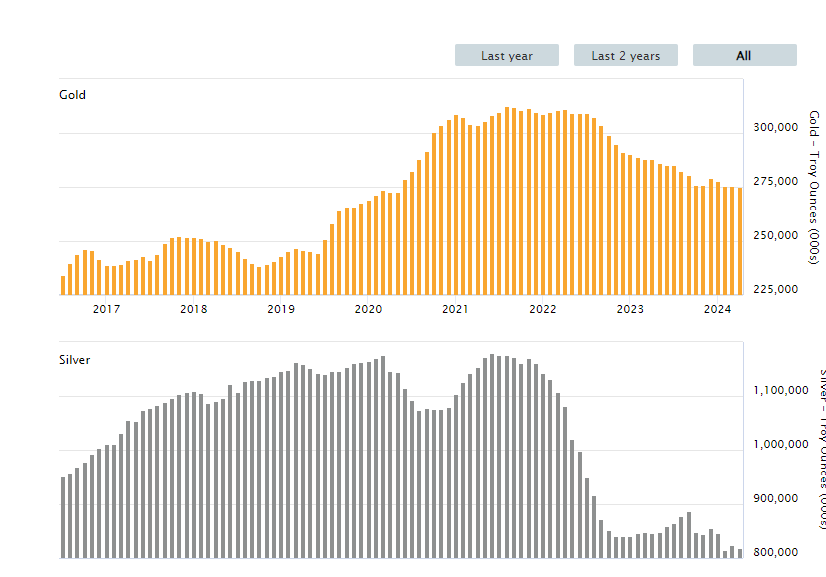

Could it be that the clearing banks might be artificially lowering the price of silver because they are running out of physical inventory to settle outstanding contracts? In fact, London’s silver vaults are almost barren.

Interestingly, a similar “strange” event occurred in late 2023 just before the price of Silver started to soar: HSBC shifts part of US precious metal trades to UK. Was this a maneuver to quickly fend off the first short squeeze attempt and mitigate losses? Intriguingly, in the last months of 2023, the Silver price moved up from ~$21 in October to ~$25 when it started to “cool down,” coincidentally after HSBC’s move.

As you can see from the final chart below, while the “fixing” price continues to rise, the clearing one does not. Could this be a (clumsy) attempt to avoid reporting mounting losses on derivatives short positions to regulators? This question remains open to interpretation.