Over the past few weeks, I have been delving into the “buy now pay later” (BNPL) phenomenon to determine the extent to which this sector could pose a risk to the financial system.

Firstly, BNPL is not a “new thing” at all, but rather, it is the evolution of what was a few years ago known as “Marketplace Lending”.

Marketplace lending is a platform-based financial service where individuals or institutions can lend money directly to borrowers without going through traditional banks. These platforms connect borrowers seeking loans with investors looking to earn returns on their capital. Marketplace lending involves the provision of loans, typically for purposes such as debt consolidation, personal expenses, business investments, or education. These loans often come with fixed terms and interest rates, usually bearing interest, which can vary based on the borrower’s creditworthiness and the loan term.

Unlike BNPL today, Marketplace lenders must comply with various financial regulations, and platforms often perform credit checks and risk assessments to determine borrower eligibility.

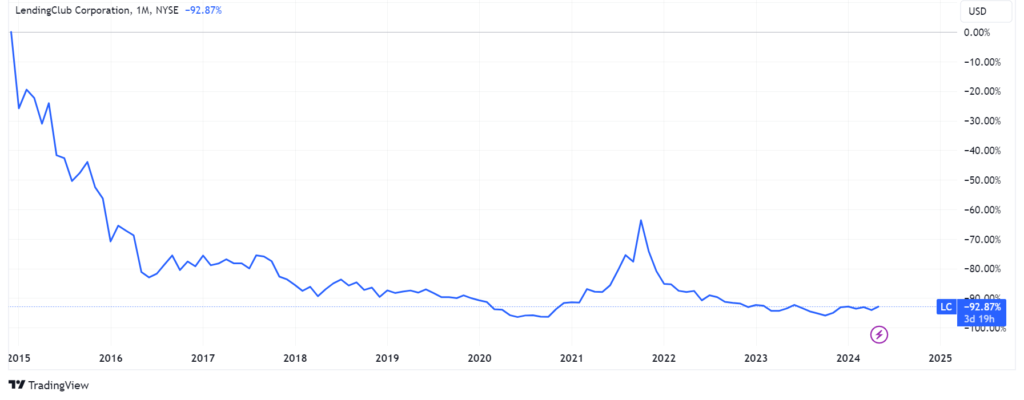

What happened to “Marketplace Lending”? The chart of the largest marketplace lending company back in the day, Lending Club, is self-explanatory. Fun fact, this company never traded above its IPO price, what a remarkable “pump and dump”.

“Buy Now, Pay Later” is marketed as a type of short-term financing that enables consumers to make purchases and pay for them over time, often without interest, as long as payments are made on schedule. BNPL services are typically used at the point of sale, both online and in physical stores. But, if the consumers don’t pay interest, then who does? The vendors. And what do you think vendors would do to recover that cost? Increase prices, of course.

Indeed, BNPL not only artificially inflates retail sales by allowing those who cannot afford to buy to nevertheless purchase an item, but it is also very inflationary since the costs will be spread out on the prices. Therefore, even those customers who purchase without using credit are effectively being burdened by the scheme. Approval for BNPL is often quick and may involve a soft credit check or no credit check at all, making it accessible to a broader range of consumers. However, the scary part of it is that BNPL is nearly entirely unregulated. For example, with regard to the US, only the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency issued a “Guidance on ‘Buy Now, Pay Later’ Lending” late last year.

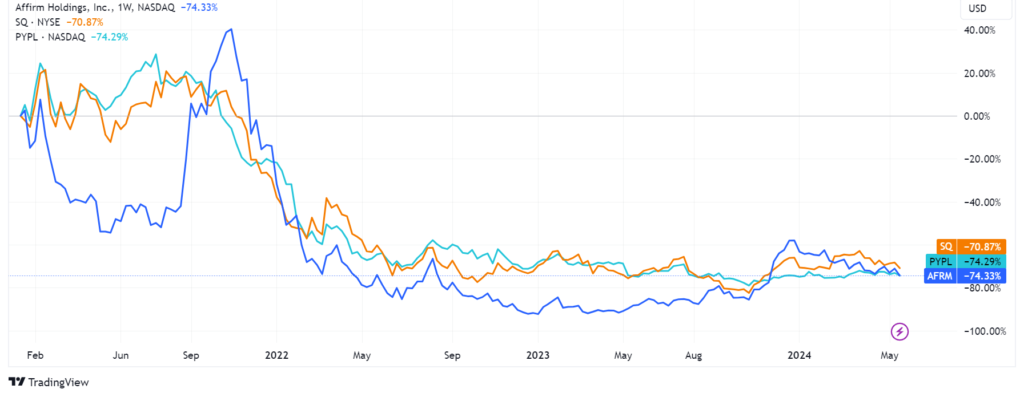

Are BNPL companies thriving and proving this model of loose micro-credit is definitely more sustainable and profitable than the Marketplace Lending one? Well, you be the judge.

At this point, I started to look for a trail to understand where the money to support BNPL is coming from since, for the most part, banks are trying to stay at a safe distance from this form of Subprime Consumer Lending. This is when I stumbled upon an incredibly well-written paper from the BIS: “Buy now, pay later: a cross-country analysis“.

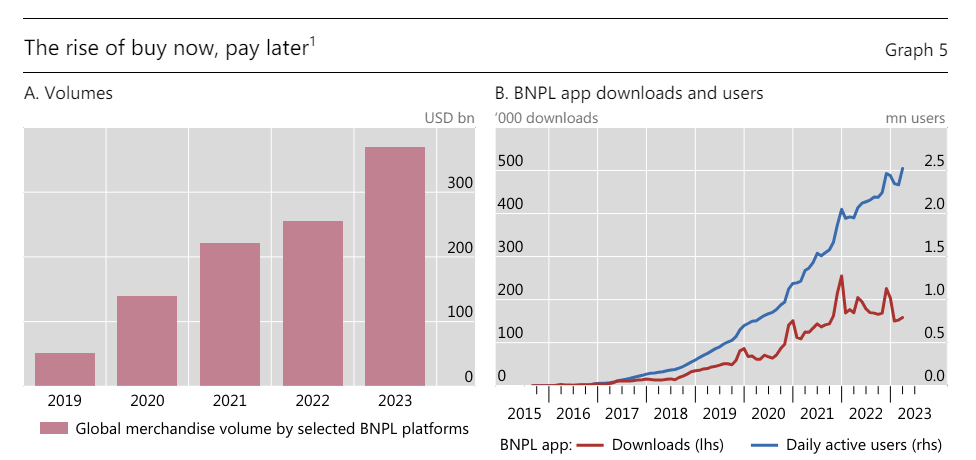

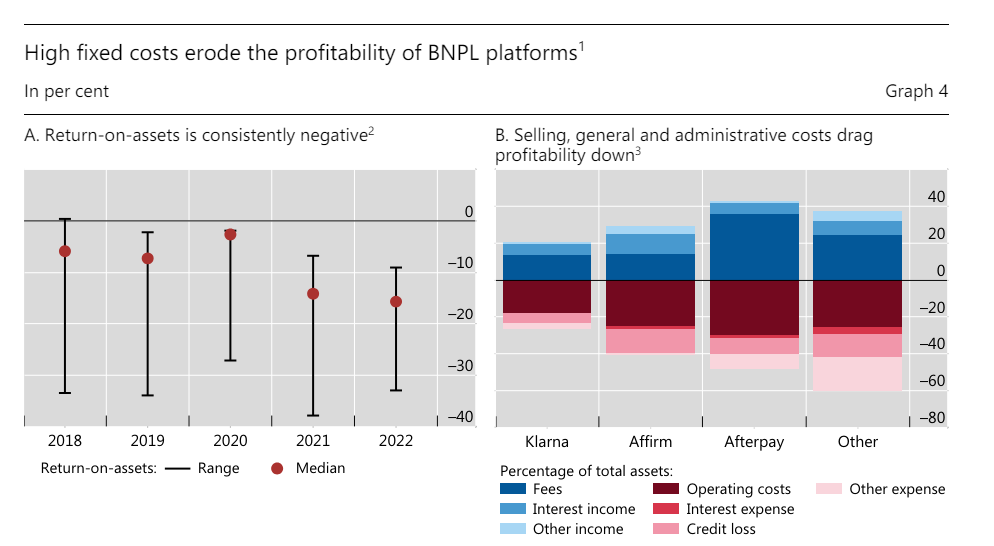

Firstly, despite its exponential growth, the one touted by investment banks and mainstream media as a sign of the “success” of BNPL, as you can see in the charts below, BNPL is chronically unprofitable (no wonder banks stay at a safe distance from it…).

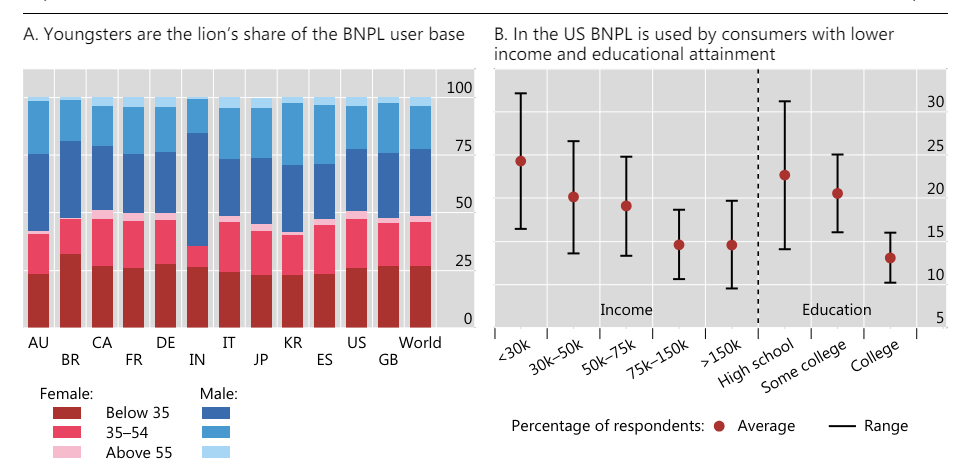

Why is BNPL a form of (very risky) Subprime Consumer Lending? Similar to the infamous “NINJA” subprime mortgages of the GFC, here again, we see that the vast majority of the borrowers are “No-Income, No-Jobs and No-Assets” ones.

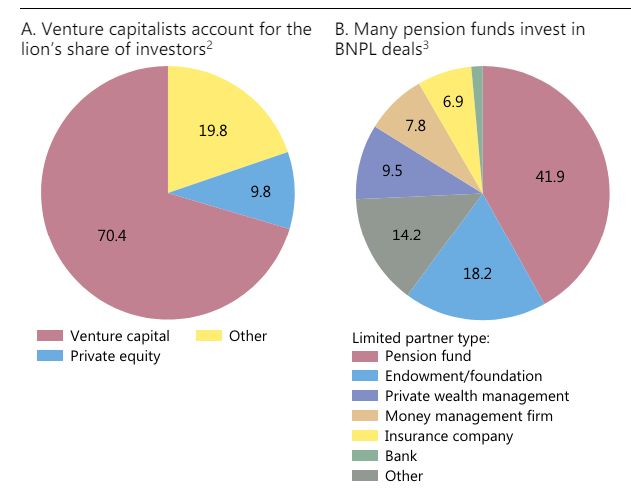

At this point, you’re probably wondering who in the world is financing this radioactive corner of the lending market. This is when I was taken aback. As you can see in the chart below, the equity portion of BNPL operators is being funded by Venture Capital and Private Equity (fair enough) that, as shown by the charts above, only care about offloading their investments to retail investors through overpriced IPOs (as usual). However, who is financing the liabilities of BNPL operators, allowing them to continue their unprofitable activity and damage the overall economy at the same time? Almost 50% of those are financed by pension funds, followed by foundations, Private Wealth Management, and Money Managers. That’s right, many people’s savings are being invested (likely without their knowledge) into NINJA Subprime Consumer Lending.

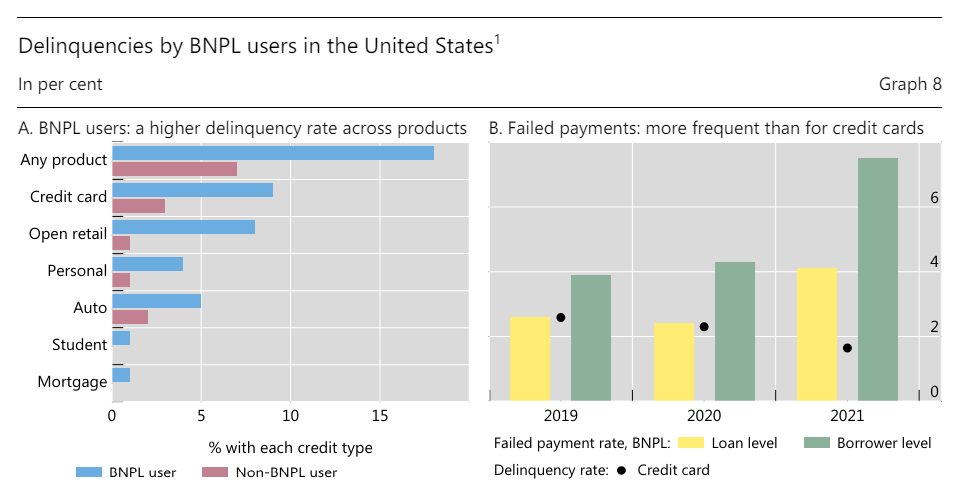

Unsurprisingly, delinquency rates are much higher than the (already risky) credit cards. But what’s even worse is that these rates are constantly rising as more people are being choked by inflation, which, paradoxically, is also made worse by these forms of maverick consumer lending.

What is the total size of the liabilities linked to BNPL? Since there is little to no regulation and no requirement to report these to credit bureaus, the best estimate available puts them at ~$232bn in 2024, up from a handful of billions in 2019. Incredibly, this pattern strongly resembles the meteoric growth of Subprime and NINJA loans between 2005 and 2008 (“The NINJA that Broke the Financial System“) with only one difference: this time, it’s the “shadow banking” driving it, and as a matter of fact, this, now very big problem, is well kept in the shadows…

~$232bn in liabilities? Why do LP’s finance these if there is no apparent return and enormous risk?